Ghaith is a Syrian refugee who fled to Sweden, by way of Lebanon, Turkey, Greece, Serbia, Austria, and Germany. He left his wife and mother to try and build a life for them that won’t involve car bombs and streets littered with body parts. He walked for miles, hid in train bathrooms and pickup trucks, and helped care for a pregnant woman and her toddler on a tiny boat that barely made it to shore. He cried when he finally reunited with his brother he hadn’t seen in three years.

I read Ghaith’s story in The New Yorker, from the comfort of my bed that was shipped from San Francisco to Perth by a company that wants to help ease my transition to a new country.

I recently chaperoned a field trip to the Freshwater Bay Museum, which, despite its name, is neither an aquarium nor a museum. It is an activity center where children can experience the lives of Australian settlers in the 1860’s. Twenty-four children in polyester blue school uniforms scrubbed tea towels on washboards, made scones out of crushed wheat, and were assigned new names like Emma Atkinson and Benjamin Sutton.

The children were asked to line up single file and take a seat in a classroom that was decked out with wooden pews and slate boards. “Girls up front, boys in back.” Pip, our tour guide who, up until this point, had been patient and kind with the children, tied on a white apron and announced she was now Mrs. Herbert.

Mrs. Herbert checked fingernails for dirt and slapped desks with her ruler. “Are you being naughty, Sarah Gallop? Do you want me to whack you?” “No.” “No, what?” “No, Mrs. Herbert.”

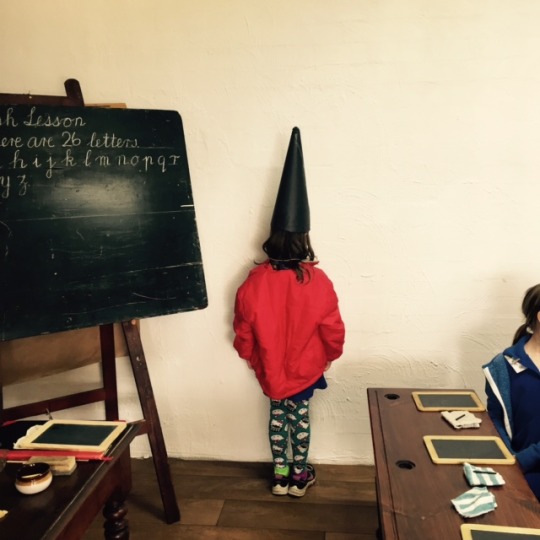

The children were given a spelling test. Pip asked for a volunteer to pretend to have failed. My daughter’s friend Daisy raised her hand high. Mrs. Herbert said, “Charlotte Yates, you have done very poorly on this test. Come here this instant.” Mrs. Herbert reached behind her desk and pulled out a tall cap with the word “Dunce” on it. For the remainder of the class, Daisy faced the wall, giggling with delight.

“Let’s play Olden Days!” Simone yells out to Daisy, as they run to our house after school, zipping past kookaburras and jacaranda trees. “I’ll be the student and you be the mean teacher,” Daisy commands, tossing her backpack on the floor and pulling off her sneakers. For hours, the girls speak very sternly, pretend to whack each other with rulers, and write the alphabet over and over. I knock on the bedroom door and ask if they want a snack. They tell me they’re not allowed to eat. “We might get whacked!” they shriek.

I’d bet my life these girls will never spend a week on a tiny boat with scared strangers, vomiting into ziplock bags and tossing them overboard. But I’ve never had to bet my life.